STORIES FROM THE VALLEY

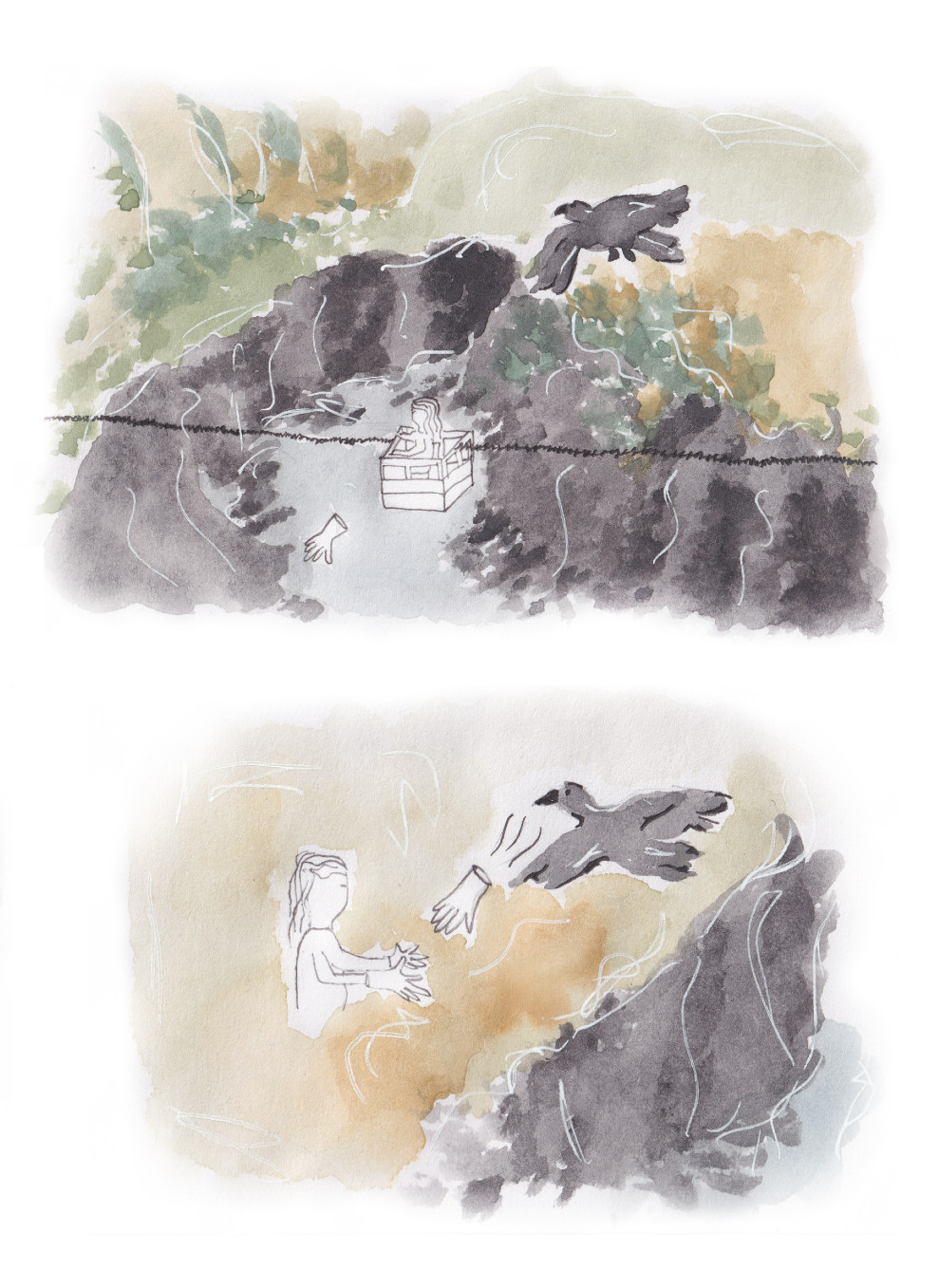

GOD REVARDS FOR THE RAVEN

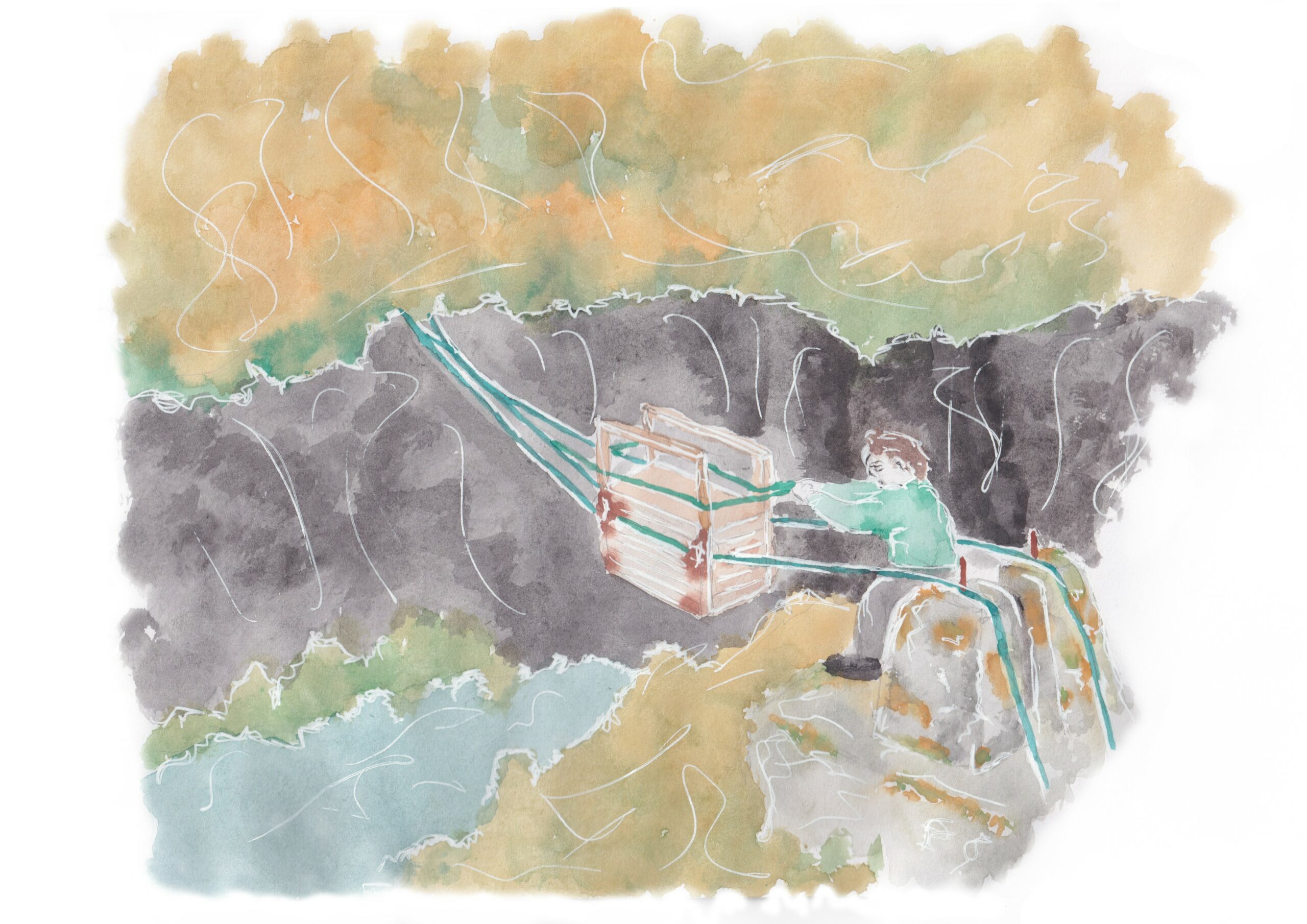

Once upon the time Stefán and his mother were crossing Jökla on their way to Egilsstaðir. In order to cross the river, they had to use a cable wagon, on the way over Stefán’s mother dropped her white glove down into the canyon. Immediately they thought the glove was lost forever because what went down into the river never returned. They continued their journey across the river and in the same breath they began their walk on the other side, a raven plunged into the canyon, picked up the glove and dropped it on the riverbank on the side where they were walking. An old Icelandic phrase:

’’God rewards for the raven’’ was particularly appropriate for this incident. Farmers in this area used to respect the raven and fed them in the cold winter season.

“OUR BIG CITY”

In Efra Jökuldalur the winters are often very heavy, and roads can become difficult or even completely impassable. However, people found their ways and it was common in the upper part of the valley that children travelled on motorised snow sled to get to school at Skjoldjolfsstaðir. The oldest child usually led the trip and the younger children sat at the back of the snow sleds. Due to the hard weather conditions and the amount of snow blocking all roads, children were routinely staying in the school’s dormitory often for a month at a time. The locals however never felt trapped, this was their big city and they lacked nothing.

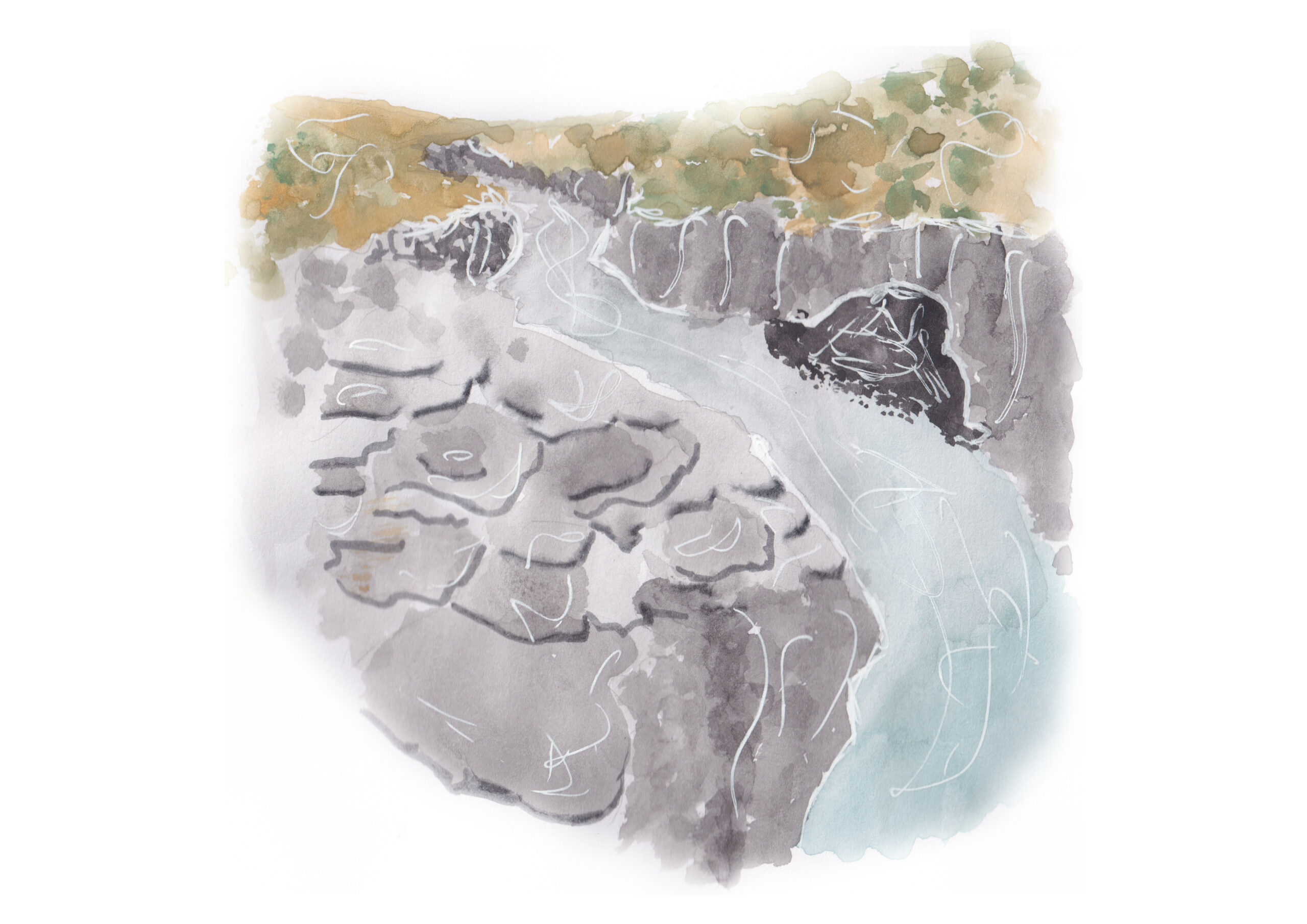

JÖKLA

Jökla is a large river (150 km) that flows through Efri-Jökuldalur (upper valley) and characterizes the place with the separation it creates. There are many stories of when the people who lived on either side of the river had to communicate but could not cross the canyon because of the river Jökla. Then they shouted across the canyon and they say it is a certain art to shout over the canyon and not something that everyone can learn how to do. They had to think of how sound travelled across with the wind, so they needed to be situated correctly and of course shout loud enough. In conversation with the habitants in the area it becomes clear that they feel a strong connection to the river and they often personify the river. One habitant said for example that when they started preparation for Kárahnjukar dam; “I feel like something will happen, maybe she will get revenge somehow “.

HRAFNKELSSAGA FREYSGOÐA

Hrafnkels saga Freysgoða is one of the Icelanders’ sagas. The story describes the struggles between chieftains and farmers in Hrafnkelsdalur at the upper valley of Jökuldalur in the 10th century. The eponymous main character, Hrafnkell, starts out his career as a fearsome duellist and a dedicated worshiper of the god Freyr. After suffering defeat, humiliation, and the destruction of his temple, he becomes an atheist. His character changes and he became more peaceful in dealing with others. After gradually rebuilding his power for several years, he achieves revenge against his enemies and lives out the rest of his life as a powerful and respected chieftain. The saga has been interpreted as the story of a man who arrives at the conclusion that the true basis of power does not lie in the favour of the gods but in the loyalty of one’s subordinates.

The saga remains widely read today and is appreciated for its logical structure, plausibility, and vivid characters. For these reasons, it has served as a test case in the dispute on the origins of the Icelandic sagas.

CABLE WAGONS

The cable wagons used to be one of the main characteristics of the valley. They used to be the main method of transport in the valley around 1900 and were situated at almost every farm. The last cable car was closed in the 1970’s, the last of them being at the farm Merki. It was common for the roads to be impassable most of the winter and the cable cars were then used to transport products and goods. There are many stories of people crossing Jökla in cable wagons which could be very dangerous and sadly there were some fatal accidents where people fell into the river.

In the winter once the river managed to freeze the locals felt the freedom as they could cross the river without worry. In the summer it was riskier to travel in the cable wagons because the forceful currents could get very strong in the river. The locals often say that what went into the river never returned.